Early Career Profile: Rare Disease PhD Researcher Jennifer Heritz

30 Jan 2024

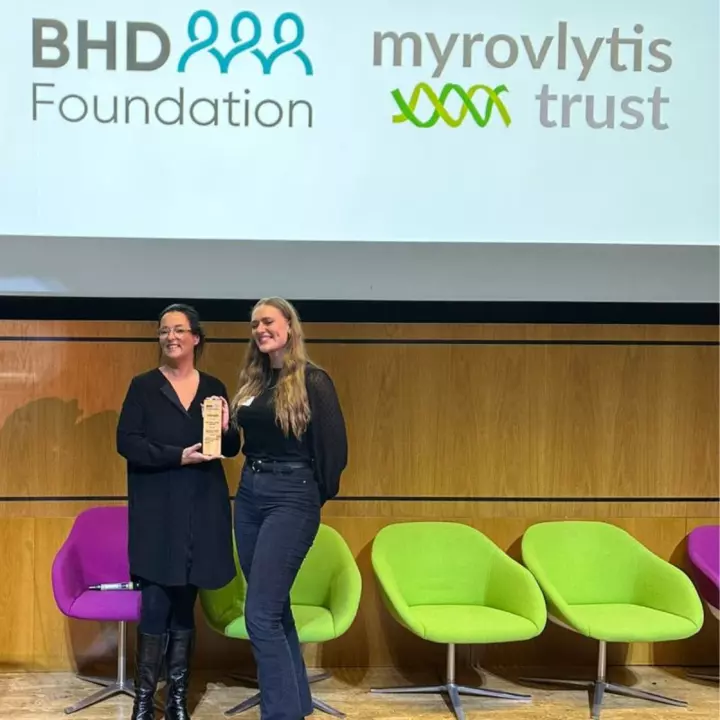

Jennifer Heritz is a PhD research candidate in the departments of Urology and Biochemistry + Molecular Biology at State University of New York - Upstate, working under the supervision of Dr. Mehdi Mollapour. At our BHD and Folliculin Research Symposium in London last year Jennifer presented her research abstract on the FCLN gene function in tumour suppression and won our Dr Anna Webb Award for Best Early Career Researcher. Here Jennifer shares her motivations and goals for working in the rare disease research field.

What made you focus on rare disease research?

I always loved my science courses. I went to an undergraduate institution with a lot of health-profession programs (like physical therapy, physician assistant, nursing, etc), and I saw my peers being able to directly help people. I also wanted to help people, but I didn’t want to stop learning about science. When I learned about biomedical research, I saw a way to do both.

I began focusing on rare disease research when I chose which research lab to join in the beginning of my PhD program. Part of my decision was based on how translational the research could be—knowing that my work could help patients in clinic is very important to me. I’ll never forget while I was in my undergraduate studies, trying to decide if I wanted a PhD, I randomly decided to watch a documentary television series called “Diagnosis”. In it, a physician at Yale (Dr Lisa Sanders) tries to help patients with rare illnesses searching for a diagnosis and cure by posting the symptoms in her New York Times column. They try to find answers from the huge population of readers when the doctors that patients had seen already couldn’t help. I remember one episode in which a little girl was suffering from unexplained fainting spells, seemingly caused by a very rare mutation in one gene. By having her story spotlighted on the column, her family found a community of others all over the globe that were going through the same thing.

Importantly, a scientist reached out. She had been researching that specific gene for 20 years but had no idea that there was a community of patients with these mutations. The patients got to meet with this researcher and talk about what their hopes were for a cure. It was incredibly moving to see how research on a seemingly niche topic can have such an impact on a family. My day-to-day work is quite far removed from patients themselves, but it’s stories like this—and those from patients I met at this year’s BHD conference—that make all the hard work worth it. I took that story with me as motivation when applying to graduate schools and research labs, and I continue to have it with me as I work today.

How did you get to where you are today?

I credit all my successes to my family and my past mentors. I’m the youngest of four kids, and they all made sacrifices so I could get to my classes and my extracurriculars. I played volleyball throughout high school and college, and that opportunity taught me a lot about resilience, commitment, and teamwork. I was fortunate to have a great coach that fostered these life skills and taught me a lot, along with supportive faculty that helped me believe I could pursue science as a career.

What skills have you developed in your professional career?

Along with all the technical skills I’ve learned in the lab, some of the major skills I’ve developed are:

- Project management and Organisation: There are always lots of projects to juggle, and it’s up to me to make sure they’re pushed forward every day.

- Communication: Understanding how to communicate my project to people with all levels of scientific background is not automatically easy, but I believe it is extremely important.

- Critical thinking and Persistence: Research requires you to think deeply about a problem from new angles constantly. To make progress, you must be okay with being wrong and trying again.

What do you love about your job?

Two things are tied for what I love most.

The people: Research is a tough job—it requires tons of time, planning, and careful thinking—then still sometimes experiments don’t work. Being surrounded by people that can and want to help are a game changer.

Learning new things: I’m not bored at my job! I love reading about what we study. I find it really cool.

What are your future goals?

To continue working in science and love what I do.

What advice would you give to people who hope to achieve similar goals?

Reach out to people. I was super shy, and afraid to really be open about any of my goals until I was 100% sure about them. But being 100% sure about something is rare in life, and it’s much better to open yourself up to help. At the end of the day, scientists are still just people. Our lab often has undergraduate students getting research experience, and we include them in things for PhD students (like journal club) so they can see how graduate school is. That’s something I wanted to do more at the undergraduate level but never got the chance (thanks, covid!).